When is it okay to call people out?

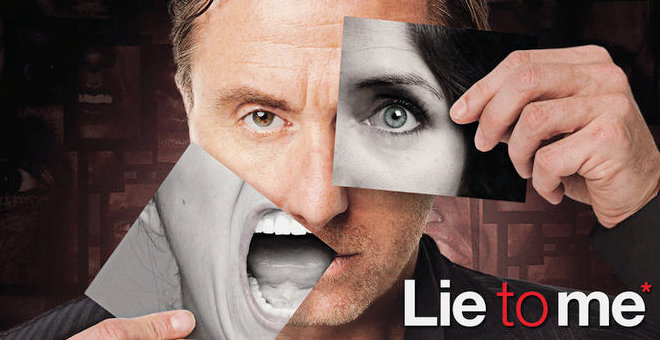

One of the most common phrases that I hear when discussing what we do at EIA is something along the lines of, “Wow! Your wife and kids must hate you!”. My usual response is to laugh it off, as the concept of the perpetually cynical behaviour analyst, similar to Cal Lightman (played by Tim Roth in the Lie To Me TV series), interrogating family members makes for humorous anecdotes in theory. But in reality, the message of “Don’t take you work home with you!” is never more true.

Just because you see how someone is feeling, it doesn’t always mean you should call them out

Now don’t get me wrong, the ability to notice those subtle shifts of behaviour that deviate from the norm when having a conversation with those I love can, and often does, give me an insight into the emotional state or thinking processes of my family. The key question to ask here, though, is… “What do you do with that insight?”

One simile for the skill set of behaviour analysis, mentioned in Paul Ekman’s writing, is that people are similar to bags (you choose your preferred container… handbag, clutch purse, leather messenger bag, briefcase, etc). We are all bags that contain our thoughts, opinions, values, emotions, biases, and prejudices. And for the most part, when we meet people, our bags are closed, and we decide what we want to remove and show those people and when we do that.

But there are times when, in the heat of the moment or when our guard is down, our bag is left open, just a little. Now, the trained behaviour analyst can see inside the bag and get a glimpse of our hidden content… But should they mention what they’ve seen? Indeed it’s hard not to see or hear something as it appears to us, but it is well within our power to choose NOT to mention what we’ve seen or heard.

This can be all the more powerful a concept when relating to those we love. We want the best for them and we want them to be happy, safe, and healthy. So, when their ‘bag’ is slightly open and I see something that I “perceive” to be counter to their health, safety, or happiness I have a duty to mention it, right? Not necessarily.

I consider myself to be an empathetic, emotionally intelligent, and reasonably intelligent chap, but let me tell you right now, I have made mistakes. There are times when it is a gift to know when you are potentially being deceived in high-stakes contexts, but in a personal family context I have ruined surprises that have been lovingly planned for me, I have alienated friends, I have made my children angry, and I have upset those I love by highlighting emotions that they were not ready to process.

Thankfully, these are rare occurrences and typically occurred when in “work” mode, perhaps when returning from training our courses away from home, or having just finished a coaching call with a student. But that’s no excuse, and these moments have taught me valuable and sometimes painful lessons.

It’s preferable to foster relationships based on openness and honesty, doing what we can to give those we love the sense that they can talk to us when they feel the need. I trust that my family feels that, IF they need to share their woes, vent their emotions, or just talk something through, they can do so in their own time.

Behaviour analysis gives us far more information about people than is openly shared and there are times when something does need to be said or you do need to talk. It’s not easy to say or do nothing when we see that others are in pain or when we “think” we can help. But often, assuming we have fostered an honest and caring relationship, the best thing we can do with our observations is exactly that… Nothing.